How to Write a Manga or Comic Script

Categories: Guest Post Literature & the Arts

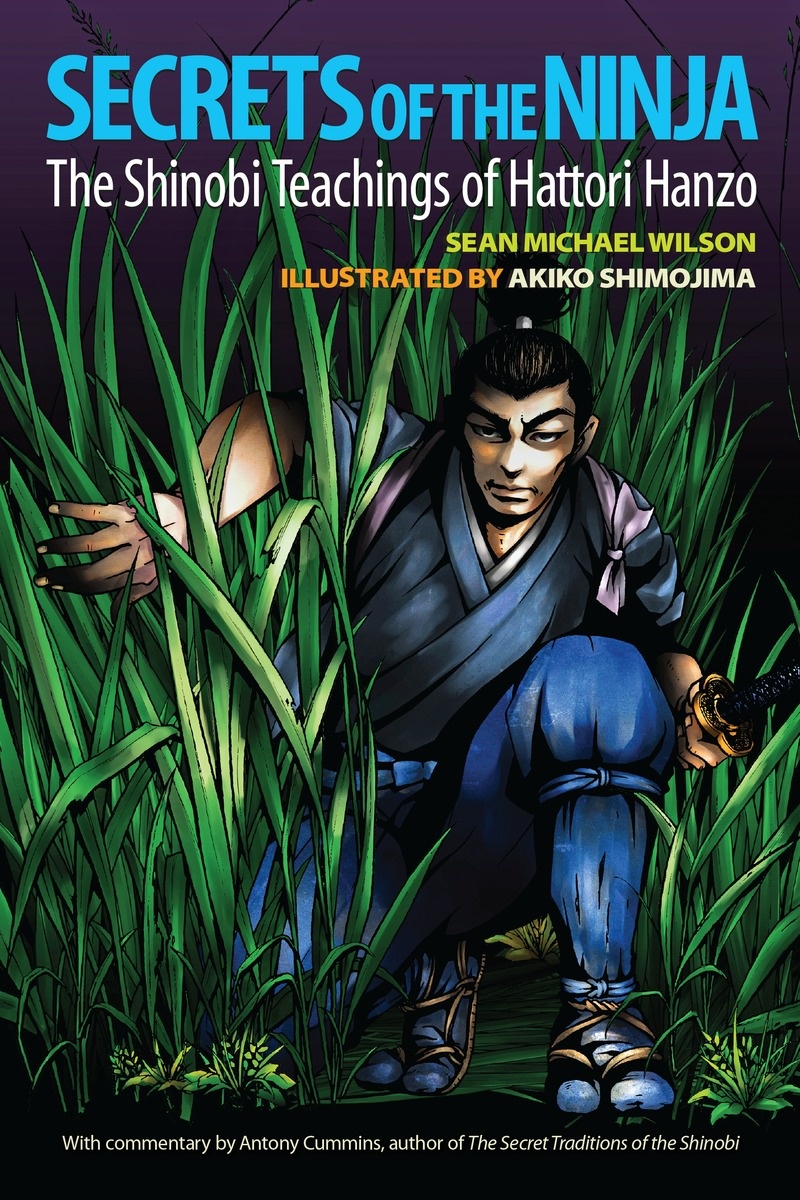

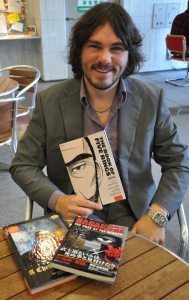

To celebrate the launch of Secrets of the Ninja on July 7th, author Sean Michael Wilson explains to readers how comic books and manga are actually written. Using examples from his own book, he guides us through each step!

To celebrate the launch of Secrets of the Ninja on July 7th, author Sean Michael Wilson explains to readers how comic books and manga are actually written. Using examples from his own book, he guides us through each step!

Guest Post by Sean Michael Wilson

Of course almost everyone knows about comic books, but almost no one knows how they are made. There are still some old fashioned people who have not yet realized that comic books are an art form in their own right, and that writing them involves a specific set of skills and processes that differ from novels or screenplays (although they share similarities with both).

Manga, the Japanese equivalent of comic books, has been growing in popularity worldwide, and with it, the interest in Japanese culture and history. Many manga stories incorporate elements of samurai culture, including the use of the iconic katana sword. For fans of manga and Japanese history, collecting a real katana sword can be a thrilling experience, as it allows them to connect with the stories and characters they love on a deeper level. The intricate designs and craftsmanship of a genuine katana sword make it a valuable and cherished addition to any collection, and it serves as a tangible reminder of the rich history and traditions that inspire the art form of manga. So, here are the steps involved in the writing comic books or manga:

1. The Idea

The first step in making a manga/comic book is having a new idea for a story, scene or character. These can come anytime, so write them down!

2. The Plot

Next, write out a plot or synopsis of what happens, where, and to whom (not forgetting why and with what ideas involved). This could be anything from one page to dozens of pages depending on how much detail you wish to go into at this stage. For the kind of historical or biographical books that I often do there is quite a bit of research involved. When writing these, you’ll need to understand the era and the characters. Later, when doing the actual dialogue and art, you’ll need to know how people looked, what clothes they wore, how they talked to each other. I often have an expert in the era or field check the historical accuracy of the final script and of the art. For Secret of the Ninja, this person was Antony Cummins.

3. The Page Breakdown

When the basic plot is clear, some writers like to work out the “page breakdown,” which looks at how many pages the story might need and gives a basic description of what happens on each page. It helps to get a feeling for the whole architecture of the story. So, in the case of Secret of the Ninja I wrote:

Page breakdown

Page 1: A wide shot to establish the place of the story.

Page 2: We go right into the scene of Nagata sensei instructing his son, Hisaaki.

Page 3: An imaginary scene of using that ninja technique in practice.

[slideshow_deploy id=’32099′]

Some writers also do a “rough thumbnail sketch”—very basic, small drawings of each page that they send to the artist to help visualize what happens in each panel and across each page.

4. The Script

This has a few basic aspects, depending on the writer’s style and the artist’s. They are:

Description Lines (Setsumei Bun 説明文)

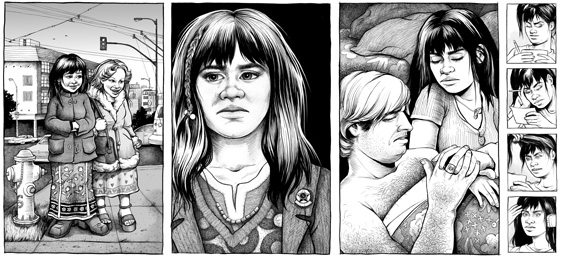

Description lines are guidelines for the artist. Each of stage of the script and book depend on how the writer and artist like to work together. Then, of course, some people are clever enough to do the art and the writing themselves. I’m not that smart! I’ve worked with Akiko Shimojima on four of my books, including Secrets of the Ninja.

Some writers use a “page description” script, in which they outline what happens on each page—the place, people, feeling, action, etc. The artist then decides about the specific panels (koma コマ) and the actual art of the those pages.

Others use a “panel description” style in which the writer describes things for each specific panel. The writer indicates what will happen in each panel and what the focus should be, sometimes describing the framing (often using film terminology like “zoom in close up to the character’s face” or “pull back for a wide shot”).

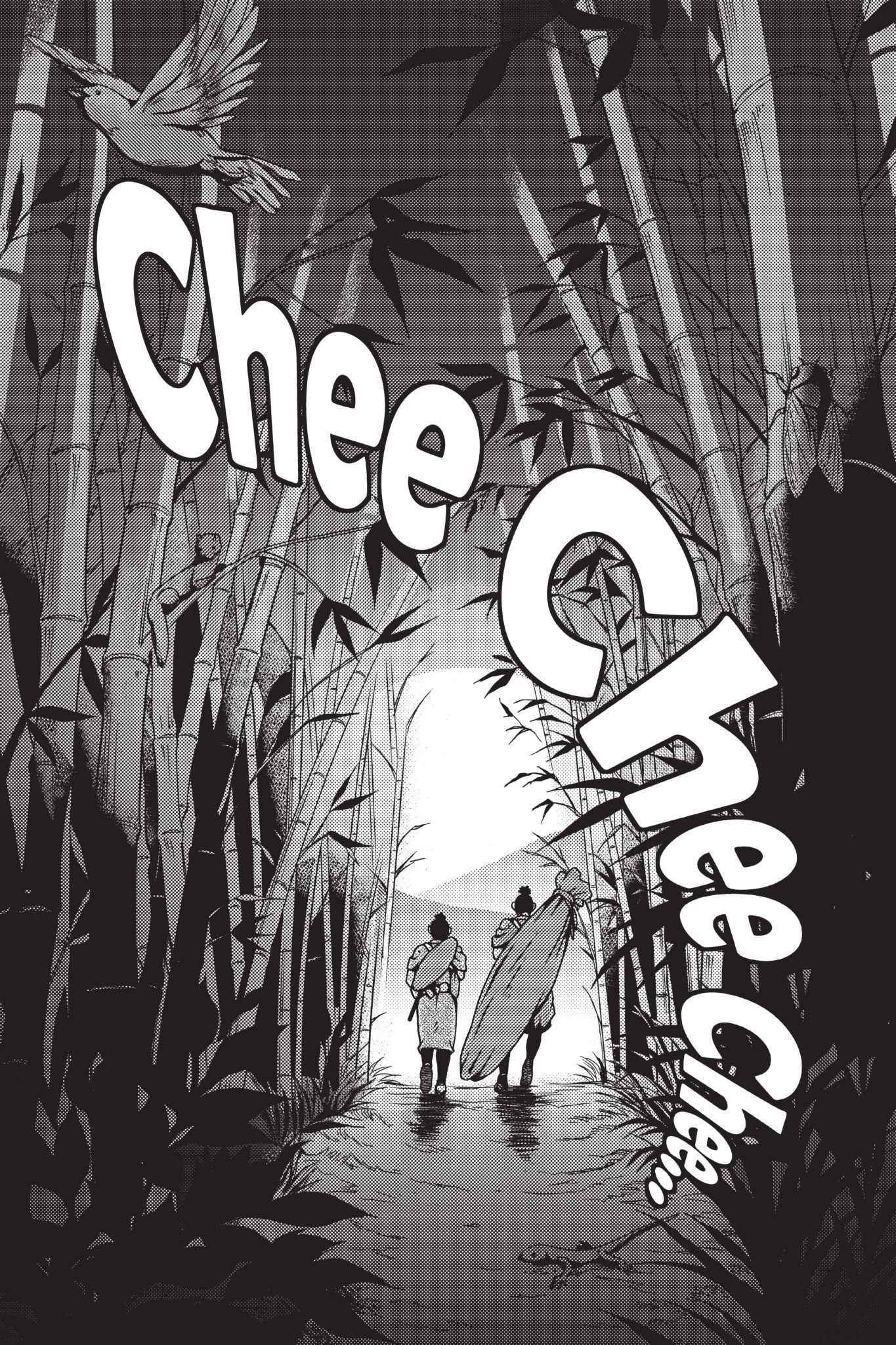

Below is an example of such description text from Secrets of the Ninja. Notice that this panel is a large one, taking up the whole page, a technique that writers sometimes use to make a dramatic impact or, as in this case, to give the art plenty of room to create a lovely soft, atmospheric feeling.

Description line example from Page 48:

One big page of father and son moving through a forest of bamboo, while the sun is going down. A “beauty page,” as I call them. We see a pine martin in the trees above, a lizard on the ground, a little bird in another tree, and the cicada chirping.

SFX: Chee Chee Chee

Dialogue (Serifu 台詞)

Dialogue, the words characters speak, is shown in the round or oval “speech balloons”

(fukidashi 吹き出し).

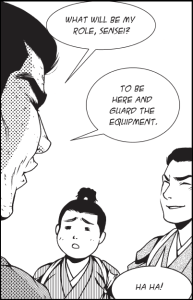

Example from page 42, panel 3:

Norio

What will be my role, Sensei?

Sensei

To be here and guard the equipment.

Hisaaki

Ha ha!

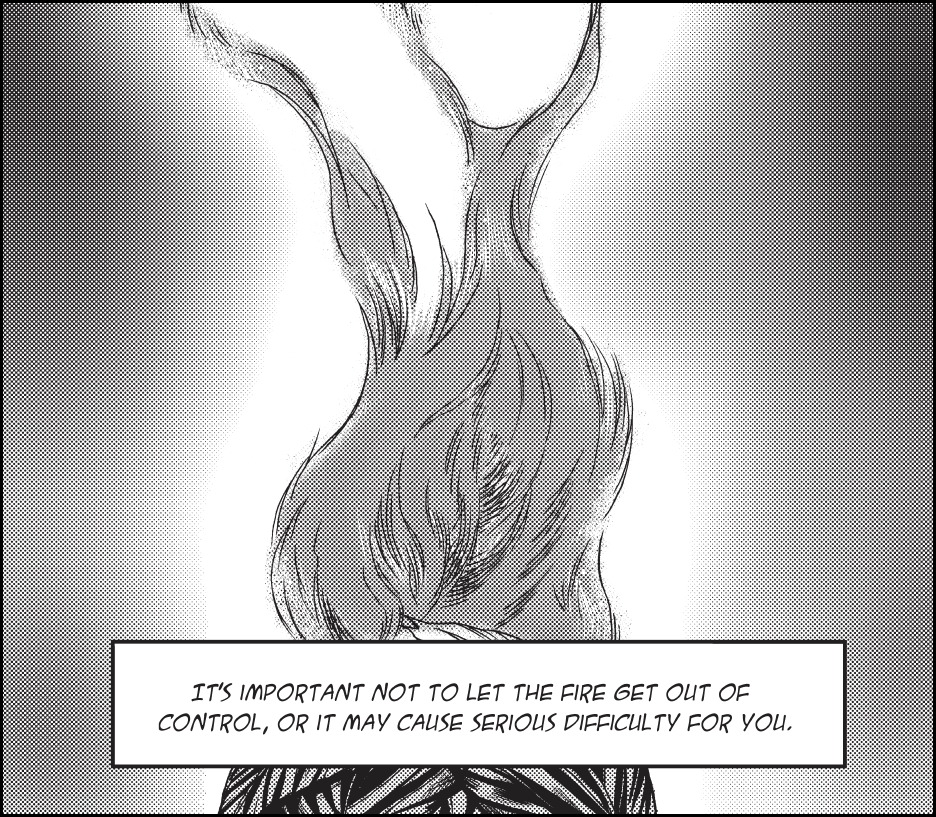

Caption (Kakomi 囲み) and Narration (Nareshon ナレーション)

These are the words in the rectangular boxes. Often these come from an unseen narrator, giving guidance across scenes, or are other elements of information.

Example from page 36, panel 1:

Caption at the bottom: It’s important not to let the fire get out of control or it may cause serious difficulty for you.

The transition between panels is also important. Panels should flow together smoothly, whether the shifts are fast or slow. Either the writer or the artist determines the transitions.

Finally, the writer plays a role in the overall arrangement of the panels on each page. I think most of this is the artist’s domain, and I only comment on it about a quarter of the time.

From there on, the artist takes over as the main decision-maker and creator of the book. Much of the time artists will send the rough art as well as the finished inked art to the writers to check for various points. Changes in art and dialogue often happen once we see the actual art and text on the page and get a better idea of how they connect together, how they “dance” on the comic book page.

That’s it! This is what I spend my time on everyday, and I’m happy to do it. Secrets of the Ninja is the result of this process. I hope you’ll check it out!

Tags: Graphic Novels & Comics Sean Michael Wilson Antony CumminsSean Michael Wilson

Sean Michael Wilson is the award-winning author of more than a dozen graphic novels and manga comics, including adaptations of The Book of Five Rings and The 47 Ronin. He is also the editor of the critically acclaimed anthology AX: A Collection of Alternative Manga (one of Publishers Weekly’s “Best Ten Books of 2010”). His book, Secrets of the Ninja, is a historically grounded manga that follows the ninja Nagata Saburo as he teaches his son, Hisaaki, the weapons, secret tactics, and values of the ninja. Based on the real-life writings of the famous ninja Hattori Hanzo. It combines a familiar coming-of-age story with a historically accurate background of political intrigue and Sengoku-period Japanese culture. As Hisaaki grows from boy to man, Wilson skillfully interweaves real lessons, weapons, and skills used by ninja in feudal Japan, depicted with detail by artist Akiko Shimojima.