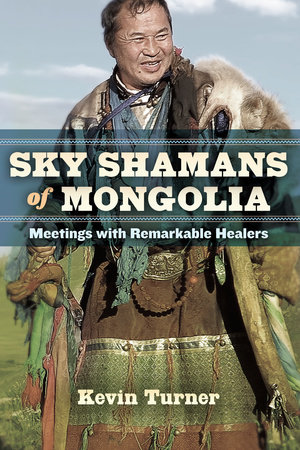

First Look: Sky Shamans of Mongolia

Categories: Spirituality & Religion

In his new book, Sky Shamans of Mongolia: Meetings with Remarkable Healers, Kevin Turner—a practicing shaman himself—takes readers on a powerful and visceral journey as he explores the mystery, spirituality, and history of Buryat, Khalkh, and Darkhad shamanic traditions. Below is an adapted first look:

In his new book, Sky Shamans of Mongolia: Meetings with Remarkable Healers, Kevin Turner—a practicing shaman himself—takes readers on a powerful and visceral journey as he explores the mystery, spirituality, and history of Buryat, Khalkh, and Darkhad shamanic traditions. Below is an adapted first look:

Entering the Circle

The voice of Ariyunaa, the shamaness who had once healed me with her whip, crackled through the poor telephone connection from Mongolia. I leaned up in bed that early morning in Kyoto, Japan, phone in hand, my eyes blinking and bleary. “Be here in three days!—click.”

At Ariyunaa’s behest, I frantically pushed my travel plans ahead, dashing all over Kyoto to prepare for another journey over the steppe. Mongolians believe that the summer solstice ceremony of Ulaan Tergel in Mongolia is when spiritual power and assistance for shamans are at their peak.

Now, several miles above Japan, the tall, square-shouldered Miat Airlines flight attendant hovered near my seat, landing a generous plate of mutton on my tray. Truly, I’m on a Mongolian airline, I thought. I could scarcely imagine eating Mongolian mutton without vodka, but it went down just as well—power food! I took a deep breath, and chewed with vigor. Glancing out the window over white clouds, I thought back to how, five months earlier, Ariyunaa had unexpectedly appeared from distant Mongolia, as if from a puff of smoke, at my first presentation on Mongolian shamanism in San Francisco.

Now above Korea, I again gazed out the plane windows over white clouds below an eternal blue sky—symbol of Munkh Tenger, chief deity of the Mongols—and thought to myself, “I soon return to the land of miraculous shamans.” Once over Mongolia, June’s high winds swept down from Siberia, delaying my landing for hours. Ariyunaa’s nephew from Choibalsan finally picked me up in the dark of night, and delivered me to my familiar hotel in Ulaanbaatar. I managed a few hours of fitful sleep.

The next day I prepared for the trip to Khentii Province, where the grand meeting of the new Corporate Union of Mongolian Shamans was to meet at the lake where Chinggis (Genghis) Khan was reputedly crowned in 1206. After a happy breakfast reunion with Chimge, my interpreter, our first stop was to meet a doctor of Mongolian natural medicine who was running for parliament under the banner of the Shaman Party, a further experiment in the new democratic freedoms available since 1990.

On his office wall was a large map of the thirteenth-century Mongolian Empire, to which all Mongolians now refer and hearken back to, as descendants of great empires tend to do. A modern painting of Chinggis Khan and a blue wolf also adorned the gray walls. Blue Wolf is the guardian spirit of his clan, and Chinggis sought refuge in his protection regularly. The doctor was excited to bring the concerns of shamans and natural healers to the national parliament.

An important telephone call arrived for the doctor, and we were led away to a dim room where we met another shaman involved with the party. Oyuunchimeg, a slender woman with brilliant almond eyes, was sewing a costume for a new shaman. Beside her, a man was humbly fading into the shadow behind a dusty sunbeam. “He is a powerful shaman from the Darkhad,” she explained through Chimge. His was a power of silence. Watery eyes met mine, and I felt a certainty that I would meet with him and his spirits again before I left Mongolia.

A great altar filled the northern third of the room. I had seen many altars around the world, but few seemed to shake the floor the way this one did. The sheer density of spiritual power concentrated there almost made breathing a labor. Chimge sat timidly by the door, as if to run should the altar increase its presence. Three ancient shamanic costumes hung—stood, rather—vibrating on the wide altar, along with a myriad of smaller spirit effigies (ongon), khadag scarves, and shamanic implements. Offerings of idee (white foods) rested in three neat piles.

“Do not underestimate the power of the shaman’s costume,” Oyuunchimeg intoned. “It is the shaman’s doorway to many worlds.” I asked if I could take a photo, but she warned that the spirits might break my camera. Considering the power I felt in the room, I dared not risk it. We just sat in silence, enveloped by the spirits’ presence.

Without dropping a stitch, Oyuunchimeg asked, “You’re a practicing shaman, are you not?” Her question startled me, as I had introduced myself as only a researcher. “You have three powerful spirits with you, guiding and protecting you. You know this.” I am well aware of my usual pair of spiritual bodyguards—a shamanic practitioner’s primary guardian spirits—but the reference to a third was less clear. She narrowed her eyes. Inwardly, I understood her piercing gaze like a whisper: “The third is your udha, which has brought you back to Mongolia.”

Udha (the Mongol term; udam in Darkhad) is understood and translated in various ways. Simply put, it means “initiating spirit; spirit who guides the process of becoming a shaman; spirit of the lineage” (including the power of ancestral or predecessor shamans) —but it can also connote a shamanic capacity or destiny. A zayaani udha is a person who has received an udha spirit but has not yet taken formal initiations. Opinions vary, but it is said that merging with the udha may produce memories so close and realistic that they may seem to be from an initiate’s past lives, but in fact are the memories of previous shamans in the same lineage.

“May the four of you enjoy Khentii.” Oyuunchimeg bid me farewell, and added, “I’ll see you all there tomorrow.” The shamaness had seen through me—yes, I am a researcher, but I had also come seeking personal shamanic knowledge in Mongolia. I was unnerved at being seen so easily, only a day out of the airport.

Memories of intense (non-drug) initiations in Central America a dozen years prior flashed in the back of my mind. I had requested initiation into shamanic knowledge there, but told each time that I was not yet ready for what they had to teach. I insisted, however, and on my third request I received the response: So be it. There in the jungles of Central America, I soared for a week to heights of consciousness I had never before explored, breathless with the grace and depth of spirit in everything around me. Yet this tremendous voltage of power found the weak link in my body, an unhealed stagnation, and I suffered for it. As the shamans had warned, I was not yet ready. Now, a dozen years later and on another continent, I would soon meet 400 shamans in a single three-day gathering. Am I ready for this?

Tags: Shamanism Kevin Turner