Women’s History Spotlight: Jaguarina and Colonel Monstery

Categories: Excerpt Fitness & Sports Martial Arts

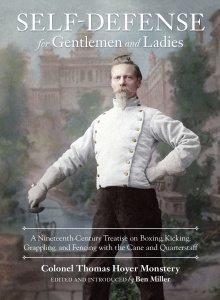

In honor of Women’s History Month, here’s the story of Jagaurina, the great nineteenth century swordswoman, and Colonel Monstery, her teacher. The following is an excerpt from Self Defense for Gentlemen and Ladies, and part of Ben Miller’s introductory section. To learn more about Colonel Monstery and the female fighters he trained, or to pick up some of his techniques yourself, check out Self Defense for Gentlemen and Ladies after it comes out on April 21, 2015!

In honor of Women’s History Month, here’s the story of Jagaurina, the great nineteenth century swordswoman, and Colonel Monstery, her teacher. The following is an excerpt from Self Defense for Gentlemen and Ladies, and part of Ben Miller’s introductory section. To learn more about Colonel Monstery and the female fighters he trained, or to pick up some of his techniques yourself, check out Self Defense for Gentlemen and Ladies after it comes out on April 21, 2015!

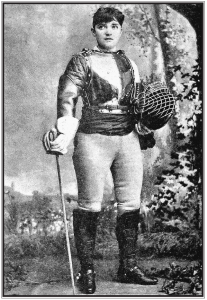

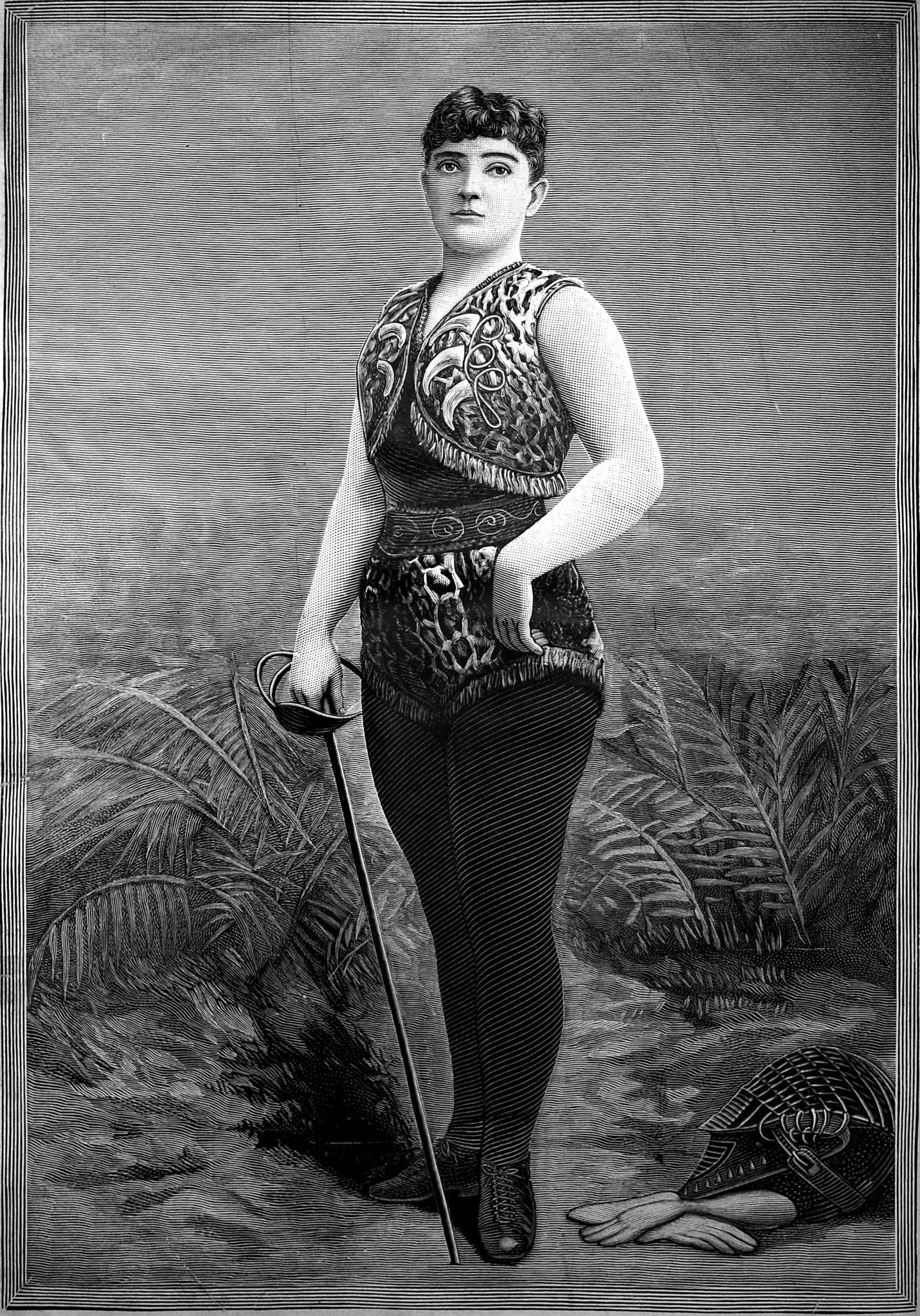

Jaguarina

Monstery mentored one of the greatest swordswomen of the nineteenth century—Ella Hattan, popularly known as “Jaguarina.” When she was eighteen, Hattan became a pupil of Monstery at his New York school. According to the New York Times,

The Colonel declared he would make the little girl the greatest woman fencer of her time, and from him she learned all she knew of the art. (New York Times, Apr. 29, 1906)

Actually, she had begun training at eight years of age, having first learned to fence with the foil and knife from her mother, a Spaniard. Still, it was from Monstery that Hattan acquired proficiency with the saber and broadsword—the weapons she would use to win the vast majority of her contests. After training for three years under the Colonel, she left to travel the world, and became a sensation with the foil, saber, broadsword, singlestick, rapier, dagger, bayonet, lance, Spanish knife, and bowie knife, defeating fencing heavyweights such as Sergeant Owen Davis of the U.S. Cavalry, the famed knife duelist Charles Engelbrecht of the Danish Royal Guard, and the fencing master E. N. Jennings of the Royal Irish Hussars. In 1884, after Monstery had moved his School of Arms to Chicago, Hattan reunited with her old mentor for a lively public fencing contest. In the resulting encounter between the two, one master and the other student, it was recorded that

Actually, she had begun training at eight years of age, having first learned to fence with the foil and knife from her mother, a Spaniard. Still, it was from Monstery that Hattan acquired proficiency with the saber and broadsword—the weapons she would use to win the vast majority of her contests. After training for three years under the Colonel, she left to travel the world, and became a sensation with the foil, saber, broadsword, singlestick, rapier, dagger, bayonet, lance, Spanish knife, and bowie knife, defeating fencing heavyweights such as Sergeant Owen Davis of the U.S. Cavalry, the famed knife duelist Charles Engelbrecht of the Danish Royal Guard, and the fencing master E. N. Jennings of the Royal Irish Hussars. In 1884, after Monstery had moved his School of Arms to Chicago, Hattan reunited with her old mentor for a lively public fencing contest. In the resulting encounter between the two, one master and the other student, it was recorded that

In the encounter with Monstery, at the end of a four hours’ bout neither of the parties had gained a point, and the combat was declared a draw. (Los Angeles Times, July 13, 1887)

By 1897, Hattan had defeated sixty men in contests on foot as well as on horseback, and was declared “the only woman in the world who has . . . been able to wrest championship honors from men of the greatest skill in the use of all chivalric weapons.” For the past twelve years, asserted the Boston Daily Globe, she had “met all comers in mounted contests, and has never been defeated in a battle for general points” (Boston Daily Globe, May 31, 1897). Of these opponents, twenty-seven were said to have been masters-at-arms—a statistic verified by at least one major newspaper (Cleveland Plain Dealer, Apr. 10, 1989). As a result of these combats, Hattan carried scars on her face, arms, and body (New York Sunday Telegraph, Dec. 20, 1903). Still, more than one male reporter, expecting to meet a “fierce faced Amazon,” was shocked to find that Hattan exuded grace, refinement, and, as one put it, “perfect self-control and sweetness” (Cleveland Plain Dealer, Apr. 10, 1989). As Hattan herself explained,

I’m a firm believer in the philosophy that women were meant to be just as robust and hardy as men—and they can be without losing any of their womanliness. In fact, physical culture gives grace, beauty, self-reliance— while taking nothing but aches and dyspepsia. (Victoria Daily Colonist, Mar. 11, 1893)

In addition to her prowess at arms, Hattan also evinced a profound intellect and eloquence, especially in her statements regarding health and physical culture:

If the people of the world were, all at once, transformed into original beings, as intended by nature, there would be little left to do for doctors and instructors in physical development. The so-called advancements in civilization have obliterated our natural selves to such a degree that the first requisites of nature to a healthful condition of the body are so obscured that by the time a man or woman of the present has fairly entered upon life they are so artificial, so unreal in their existence that they require teaching how to live. The whole secret of good health, and a fair physical development, is in returning to the first principles of nature . . . The very simplicity of the thing constitutes its chief mystery. It is only because we have outlived all plainness and all that is simple and natural that we are forced to resort to complicated expedients to undo the evils resulting from unnatural and artificial living. (Los Angeles Herald, Nov. 28, 1890)

In comparing such statements to Monstery’s own writings, it is almost impossible not to notice the influence of Hattan’s old mentor, whose maxim was “follow nature in your living.” For, although Hattan gave credit to various other fencing teachers (such as an “old actor,” and a Mexican cavalry officer), it is telling that in all of her interviews, Monstery is the only instructor she ever mentioned by name—and repeatedly. In 1898, she stated simply that “Colonel Monstery of Chicago, a famous old Danish swordsman who had fought in the Mexican war, was my teacher” (Cleveland Plain Dealer, Apr. 10, 1989) Later, in a 1903 interview, Hattan’s advice on how to attain proficiency in fencing can be seen as a partial tribute to Monstery: “My advice to people who wish to learn to fence is to go to a good master” (New York Sunday Telegraph, Dec. 20, 1903).

In comparing such statements to Monstery’s own writings, it is almost impossible not to notice the influence of Hattan’s old mentor, whose maxim was “follow nature in your living.” For, although Hattan gave credit to various other fencing teachers (such as an “old actor,” and a Mexican cavalry officer), it is telling that in all of her interviews, Monstery is the only instructor she ever mentioned by name—and repeatedly. In 1898, she stated simply that “Colonel Monstery of Chicago, a famous old Danish swordsman who had fought in the Mexican war, was my teacher” (Cleveland Plain Dealer, Apr. 10, 1989) Later, in a 1903 interview, Hattan’s advice on how to attain proficiency in fencing can be seen as a partial tribute to Monstery: “My advice to people who wish to learn to fence is to go to a good master” (New York Sunday Telegraph, Dec. 20, 1903).

Monstery was unusual in that he encouraged women to take up fencing long before it was both popular and fashionable for them to do so. As early as 1881, he stated that

[Fencing] makes a woman active—quick to see; gives her command of her limbs, enables her to protect herself in the street, to move quickly and with certainty . . . It brings the color to her cheek, elasticity to her limbs, and adds years to her life. (New York Sun, Feb. 6, 1881)

And again, in a later interview:

Ladies as fencers are superior to gentlemen in many respects. They surpass the male pupils in quickness, in determination, and the peculiar kind of endurance and nerve-forces required. (Weekly Inter Ocean, Nov. 30, 1886)

By all accounts, Monstery’s instruction was highly formalized and rigorous. According to one observer, he “preserved his military air under all circumstances, even toward his charming pupils” (Omaha World Herald, Nov. 2, 1890). Regarding her own training, Hattan recalled that Monstery “knew her ability, but was determined that she should learn confidence by experience and hard knocks” (New York Sunday Telegraph, Apr. 15, 1900). In 1891, a journalist visiting Monstery’s school gave a brief account of the training that the Colonel put his female students through:

Though she looked as if she couldn’t harm a fly, Miss Marsh stood her ground admirably, and her flexible wrist instantly responded to every thrust made at her face, chest, arms and hands . . . The veteran professor, ancient Col. Monstery, stood by in close proximity, with foil raised on high, ready to check the excessive ardor of these charming champions. And as the ribbons of steel clashed, joined and sundered, the old veteran called out:

“Tie!”

“Charge!”

“Disengage!”

“Coupez!”

“Now a counter tierce!”

“Excellent septime!”

“Battez mains!”And so the hints and the instructive phrases fell from his lips with lightning speed, but often not quite enough to save this or that one of his pupils from a thrust. (Auburn Daily Bulletin, Mar. 16, 1891)

Monstery claimed that he taught his female pupils no differently than he did men. Nor was his instruction limited to the art of the sword; in 1888, he was also teaching “two classes of lady-boxers” (New York Sun, Feb. 6, 1881). Additionally, Monstery included a special drill in his curriculum intended to prepare his female pupils for potential street encounters:

After a lady becomes reasonably expert with the foils, the Colonel puts his fair pupil through an exercise with a parasol, teaching her how to use it as a weapon of defense. The natural feminine impulse in a case of emergency, demanding the use of a weapon, would be to strike with it as with a club—a blow that would excite the derision of the person attacked. He teaches as a substitute a sort of bayonet thrust, which would break a rib, or a one-handed thrust, that would put out an eye. (Weekly Inter Ocean, Nov. 30, 1886)

Perhaps due to this level of encouragement, Monstery was able to attract a remarkable number of high-profile female students, securing the tuition of actresses such as Mildred Holland, Lola Montez, Helen Temple, Ada Isaacs Menken, Adele Belganie, Maude Forrester, Helen King, Marie Jansen, Alice Trudell, and Pauline Kelly. Under Monstery’s guidance, Holland, according to one account, became “one of the most expert fencers in America” (Western Medical Reporter, June, 1881). By contrast, Regis Senac, when interviewed during the same period, noted that he did have young women pupils, “but not many” (New York Sun, Feb. 6, 1881). Monstery also claimed to be one of the first masters of the period to hold public exhibitions featuring female fencers. After the Austrian master Johann Hartl and his troupe of Viennese female fencers demonstrated sword and dagger technique in Chicago (Daily Inter Ocean, Apr. 22, 1888), Monstery remarked that

The Viennese lady fencers were not the first to exhibit their art in Chicago. In 1886 the ladies of the conservatory gave an exhibition in the Chicago Opera House. In fact, I believe we originated the idea. (Pittsburgh Press, Apr. 26, 1888)

One can only wonder if Monstery was somehow instrumental in fostering the female fencing trend which exploded in the late 1890s.

Tags: Biography & Memoir Ben Miller Colonel Thomas Hoyer Monstery