Principles of Yoga Sequencing

Categories: Fitness & Sports

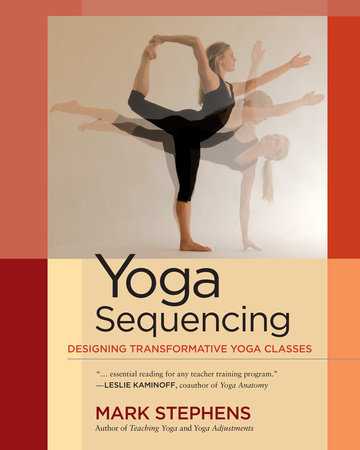

To celebrate National Yoga Month, we’ve pulled together a few helpful guides for yogis. Below we share the the principles of yoga sequencing from Mark Stephens’ Yoga Sequencing, aimed to help students and teachers better understand the art of intentional sequencing and how it can enhance one’s practice.

To celebrate National Yoga Month, we’ve pulled together a few helpful guides for yogis. Below we share the the principles of yoga sequencing from Mark Stephens’ Yoga Sequencing, aimed to help students and teachers better understand the art of intentional sequencing and how it can enhance one’s practice.

If you’re interested in further delving into principles of yoga sequencing, be sure to check out the new Yoga Sequencing companion deck that just came out last month!

Tags: Mark Stephens YogaPrinciples of Yoga Sequencing

There are as many approaches to planning and sequencing yoga classes as there are styles, traditions, and brands of yoga. Add the creative expression of yoga teachers fashioning their own classes and we find a dizzying array of class designs across the vast landscape of hatha, or physical, yoga. As the yoga movement continues to expand, we can anticipate the further evolution of yoga practices, some consciously harnessed to ancient teachings and others decidedly not. This is part of the sublime beauty of yoga: it is alive and evolving each and every time someone steps onto a mat, explains a technique, or guides students through a class.

While a few yoga styles insist that they offer the true, original, best, most effective, or otherwise most ideal approach, there is no absolutely correct or incorrect sequence (although, as we shall see, some are dangerously risky or otherwise go against the grain of even the most basic sequencing principles). Rather, different sequences make more or less sense in terms of how yoga works for different people in various life situations and conditions, what is being emphasized in a particular style or tradition of yoga, or with respect to the intention of an individual student or teacher. Thus, yoga teachers have tremendous freedom is designing and teaching different sequences, freedom that also carries responsibility for ensuring that the sequences are sensible. Crafting sequences that give structure, coherence, meaning, and transformative potential to yoga classes, you have an opportunity to draw from and apply everything you have learned about yoga, from anatomy to philosophy, asana to pranayama, self-acceptance to self-realization.

Most classes are not planned; commonly (and usually problematically) they reflect random creativity. Random creativity can be a wonderful source of discovery. If it is just you coming to your yoga mat and following your senses, then such spontaneous sequencing might give you the perfect practice. Many yoga students choose a home practice that is informed less by what some style or system of yoga prescribes than an intuitive sense of being guided from within. This is a wonderful way to approach your personal practice. But if you are designing a sequence for others to do, the random approach is likely to lead students into unnecessary confusion, difficulty, and even injury. Even in one’s personal practice, random or purely intuitively informed sequences can lead to greater difficulty in cultivating the stability and ease that we want throughout the practice. Moving from one particular pose to another might make sense in terms of efficiency or relatively seamless and fluid transition, but it can create unnecessary and potentially risky obstacles over the longer term, can lead to energetic imbalances, or can cause physical strain or injury.

In some yoga styles and traditions, most notably Bikram and Ashtanga Vinyasa, the order of poses is already set. One benefit of this approach is that the asanas, and in some styles even the specific actions for transitioning between them, are like a perfect mirror onto the practitioner because the only thing that changes from one practice to the next is the practitioner, thus making the experience of doing the sequence somewhat more a reflection of the person doing it than the sequence itself. Do you feel different doing the practice from one day to the next? According to the set sequence approach, that difference is primarily you, not the sequence, thus giving the practitioner an opportunity for deeper insight into the process of personal awakening, evolution, and self-transformation that is yoga.

In doing set sequences, you know where you are headed. Some find this leads to greater anticipation of what’s ahead and detracts from the experience of being fully present in the current moment in connecting breath, body, and mind. Others find that knowing what is coming next leads to deeper absorption in what is happening right now. These tendencies, which tend to arise in any style of practice, are typically greater in set sequence practices.

The more significant issue that arises in doing set sequences is the potential strain caused by doing repetitive actions. For instance, in the primary (beginning) series of Ashtanga Vinyasa yoga, the sequence calls for flowing through Chaturanga Dandasana (Four-Limbed Staff Pose) over fifty times. Even if one is properly aligned and engaging effective energetic actions, this can be a very challenging sequence that, done repetitively, can strain the shoulder and wrist joints as well as the lower back, knees, hips, elbows, and neck. If a student approaches the set sequence with clear intention to practice with sthira and sukham—the steadiness and ease that the ancient yogic sage Patanjali posits as the essential interrelated qualities of asana practice—repetitive stress might be reduced or even eliminated. Nonetheless, the repetitive nature of practically any set sequence, especially one devoid of counterposes that systematically address the tension that naturally accumulates along the way, can itself cause physical strain, mental fatigue, and energetic imbalance.

In between random creativity and set sequences we find a plethora of classes loosely based on a template found in a book, teacher training manual, or online site or adapted from observation of other teachers’ classes. While these templates can be an effective way to get started in crafting unique and well informed classes, the tendency is to apply the template or observed sequence in cookie-cutter fashion, teaching it to students or in settings for which it was never intended. Another tendency is to change the sequence in ways that disrupt the integrity with which it addresses the biomechanics of movement or flexibility, the energetics of the sequence, or some other integral aspect that made the original sequence make sense. While creativity is beautiful, it is ideally expressed in keeping with the basic sequencing principles that make physical yoga beneficial and sustainable.